Swiss Style Claims: Ranbaxy v AstraZeneca

Ranbaxy (UK) Ltd. v AstraZeneca AB [2011] EWHC 1831 (Pat) (15 July 2011) raises an interesting point on the interpretation of claims. To be more precise "Swiss style claims".

Ranbaxy (UK) Ltd. v AstraZeneca AB [2011] EWHC 1831 (Pat) (15 July 2011) raises an interesting point on the interpretation of claims. To be more precise "Swiss style claims".Swiss style claims get their name from the legal advice of the Swiss Federal Intellectual Property Office of 30 May 1984 (OJ EPO 581) on the patentability of compounds used in the manufacture of a medicine for the treatment of a disease. As Mr. Justice Kitchin explained between paragraphs [42] and [60] this convoluted form of words was devised to get around the exclusion by art 52 (4) of the European Patent Convention before its revision in 2000 of "methods for treatment of the human or animal body by surgery or therapy and diagnostic methods practised on the human or animal body." Lord Justice Jacob discussed Swiss style claims in some detail in Actavis UK Ltd v Merck & Co Inc [2008] EWCA Civ 444 (21 May 2008).

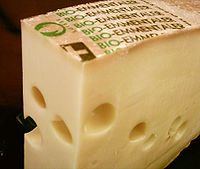

The usual context in which Swiss style claims are considered is "second medical use" - that is to say where a compound used to treat condition A is found to have healing properties in respect of condition B. In this case, however the generics company Ranbaxy wanted to import from India a drug for the treatment of gastric acid related diseases. The active ingredient of the drug was magnesium esomeprazole. AstraZeneca had a European patent for the use of this compound. Claim 1 of EP 1 020 461 was as follows:

"The use of a magnesium salt of (-)-5-methoxy-2[[(4-methoxy-3,5-dimethyl-2-pyridinyl)methyl]sulfinyl]-1H-benzimidazole ((-)-omeprazole) with an optical purity of = 99.8% enantiomeric excess (e.e.) for the manufacture of a medicament for the inhibition of gastric acid secretion."

It was common ground that the process of manufacture of Randaxy's product began with magnesium esomeprazole with an optical purity of = 99.8 % but the process involved the addition of a quantity of omeprazole racemate so that the finished product ceased to contain magnesium esomeprazole of that optical purity. Ranbaxy had obtained regulatory clearance for the sale of its drug in the UK and the only obstacle in its way was AstraZeneca's patent. Ranbaxy claimed a declaration of non-infringement and AstraZeneca counterclaimed for infringement.

Mr. Justice Kitchin gave judgment to Ranbaxy on both the claim and counterclaim. Giving the specification a purposive construction the judge held that the AstraZeneca's invention was the use of magnesium esomeprazole with an optical purity of = 99.8 % e.e. He found

"no suggestion anywhere in the body of the specification of the provision or use of any analogue or derivative of magnesium esomeprazole or, indeed, of any other active ingredient for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders or any other condition. Nor is there any suggestion that the specification provides a new way of making a medicament. The whole teaching of the specification is about the production of optically pure magnesium esomeprazole and its use in particular therapies and, for that purpose, its formulation with a conventional carrier." (para [66])

The key point is actually to be found in paragraph [35] of the judgment where His Lordship addressed Ranbaxy's argument that claim 1 was a Swiss form claim and that such claims are in substance directed to the protection of a new therapeutic use of a medicament containing a known active compound. It follows that if the claim is valid the medicament must contain that compound.

This is very much lawyers' law - indeed intellectual property lawyers and patent agents' law. Should any lawyer, patent agent or member of the public want amplification or clarification of this case, he or she should call me on 0800 862 0055 or use my contact form.

Comments