Patents - Claydon Yield-O-Meter v Mzuri

|

Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (HH Judge Hacon) Claydon Yield-O-Meter Limited v Mzuri Ltd and another [2021] EWHC 1007 (IPEC) (22 April 2021)

This was a claim by Claydon Yield-O-Meter Limited ("Claydon") against Mzuri Ltd ("Mzuri") and its director for the infringement of GB 2 400 296 for an “Improved seed drill” (“296”) and EP2051576 (“576”) also for an improved seed drill. There was also a counterclaim by Mzuri for the revocation of those patents. The action and counterclaim came on for trial before HH Judge Hacon between 24 and 26 Feb 2021. The learned judge delivered judgment on 22 April 2021 (see Claydon Yield-O-Meter Limited v Mzuri Ltd and another [2021] EWHC 1007 (IPEC) (22 April 2021). By para [155] of his judgment, he found that 296 was invalid but had it been valid it would have been infringed. He also found 576 not to be valid and not to have been infringed.

Issues

Judge Hacon considered first whether 296 had been infringed and if so whether it was valid. Secondly, he considered whether 576 had been infringed and then whether it was valid.

Patent 296

The invention for which 296 was granted relates to a method and apparatus for planting seed for crops which is to be pulled by a tractor. The invention may be used for sowing in minimally cultivated seedbeds, creating conservation tillage in which the soil between the newly sown rows of the new crop is left relatively undisturbed. “Conservation tillage” is a means of tilling soil in a manner better to conserve it, in particular by reducing soil erosion.

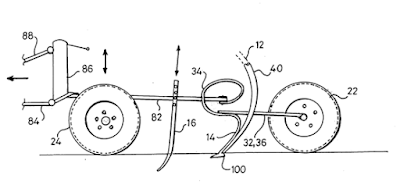

Figure 1 is a diagram of a machine that embodies the invention:

(a) a frame, adapted in use to be towed by, or attached to the rear of, a tractor,

(b) a first row of tines carried by the frame and spaced apart across the width of the frame,

(c) a second row of tines also carried by the frame and spaced to the rear of the first row in the direction of forward motion of the apparatus when in use, and the second row tines are similarly spaced apart across the width of the frame so that each of the tines in the second row is aligned with one of the tines in the first row whereby in use soil will only be disturbed in spaced apart linear regions determined by the lateral spacing of the tines, and the strips of soil therebetween will not be disturbed,

(d) a hopper means containing seed,

(e) means for feeding seed therefrom down the rear and to the underside of each of the second tines,

(f) soil levelling means carried by the frame and located in alignment with the tines to the rear of the second row of tines (relative to the said forward direction of motion when in use), so that in use as the apparatus moves in a forward direction, soil that has been disturbed by the tines is generally flattened by the passage of the levelling means thereover."

“It is settled law that to invalidate a patent a disclosure has to be what has been called an enabling disclosure. That is to say the disclosure has to be such as to enable the public to make or obtain the invention. Further it is settled law that there is no need to prove that anybody actually saw the disclosure provided the relevant disclosure was in public. Thus an anticipating description of a book will invalidate a patent if the book is on the shelf of a library open to the public, whether or not anybody read the book and whether or not it was situated in a dark and dusty corner of the library. If the book is available to the public, then the public have the right to make and use the information in the book without hindrance from a monopoly granted by the State.”

“[148] It is one thing to say that if the public is given access to information, in whatever guise, that information is made available to the public and it does not matter that no member of the public in fact took up the opportunity: cf Folding Attic Stairs at [86] where Mr Prescott said he understood that the French and German texts of the EPC convey the flavour of "made accessible to the public". Putting a publication in a library makes it accessible to the public, and so available to be read, even if no-one does: it could have been read and the law does not require you to show that it was. Similarly putting a traffic light controller on a public road, or giving contractors access to it, makes it accessible to the public and it could have been observed, and the information that could have been thereby obtained is therefore available to the public, even if no-one stops to look at it; a mat hired to a customer could have been examined, even if it is known for certain that no-one did.

[149] But it is quite another thing to say that the law treats information as available to the public when no member of the public could in fact have accessed it. If it is right as a matter of fact (as I have found that it is) that if any member of the public had tried to observe Mr Berardi in his garden, Mr Berardi would have stopped what he was doing, it seems a misuse of language to say that what he was doing could have been observed, even in theory. If anyone had tried to observe him they would not have seen anything because he would have packed everything up. In other words although any member of the public could have turned up at Skylark Point and stopped to look, had anyone done so, whether a skilled person or anyone else, he would not have been given access to any information. That seems to me to be very different from a publication left in a library for all to read if they choose, or an article left in a public place for all to see if they choose.

[150] This analysis may also provide an answer to Mr Hinchliffe's example of the inventor talking out loud in a public but empty place. I do not need to decide the point but on the view I take it would all depend on what he was doing. It is quite difficult to think of plausible scenarios where this might actually happen in the real world but if, for example, the inventor advertised a public lecture and, even though no-one came, proceeded to give it so it could be recorded for his own purposes, that would on the view I take be an oral disclosure that was accessible, and hence made available, to the public and it would not matter that no-one had in fact turned up. But that would be very different from the inventor talking out loud to himself while taking a walk along a deserted but public footpath over the moors. If in the latter case he would have stopped talking as soon as any member of the public was close enough to hear, I do not think he would have made anything available to the public.

[151] It follows that in the present case the information was not in my judgment in fact ‘made available to the public’ within the meaning of s.2 (2) PA 1977.”

(b) Identify the relevant common general knowledge of that person;

(2) Identify the inventive concept of the claim in question or if that cannot readily be done, construe it;

(3) Identify what, if any, differences exist between the matter cited as forming part of the "state of the art" and the inventive concept of the claim or the claim as construed;

(4) Viewed without any knowledge of the alleged invention as claimed, do those differences constitute steps which would have been obvious to the person skilled in the art or do they require any degree of invention?"

His Honour said at [29] that "the common general knowledge" was the technical background of the skilled person. He added that it was the knowledge that such a person would bring to bear when they are reading or otherwise considering the prior art or, as in this case, an alleged prior use. It will be taken to include information readily to hand which the skilled person would have known they could access and which they would have felt the need to access in order properly to consider the prior art. He referred to Idenix Pharmaceuticals Inc v Gilead Sciences Inc [2016] EWCA Civ 1089 at [70]-[72] and Generics (UK) Ltd v Daiichi Pharmaceutical Co Ltd (2009) 32(9) IPD 32062, (2009) 109 BMLR 78, [2009] RPC 23, [2009] EWCA Civ 646 at [25]. Judge Hacon set out such knowledge between paras [30] and [44].

"The invention disclosed has a vertical knife-like means (“the banding knife”) for creating a vertical trench in the ground and a horizontal sweeping means (“the planting sweep”) for opening a horizontal swath in the ground and thereby creating a seed-supporting shelf on either side of the vertical trench. Seeds may be deposited on the shelf on either side of the trench. Fertilizer may be placed in the trench and then ground is replaced over the seeds and fertilizer. The planting sweep allows seed placement in parallel paired rows near but not too close to the fertilizer. This may all be done in a single pass. There are also means for depth control."

“1. An apparatus for cultivating soil and sowing seed, comprising:

(i) (a) a first frame (A) carrying a row of digging tines, adapted in use to be towed by, or attached to the rear of, a tractor,

(ii) (b) a second frame, movably attached to the first frame, carrying a row of seeding tines,

(iii) each of the seeding tines being aligned with one of the tines on the first frame and spaced therefrom in a direction parallel to the direction of forward motion of the apparatus when in use,

(iv) and comprising depth wheels which in use travel along the surface of the soil,

(v) wherein the seeding depth is governed by the position of the depth wheels relative to the second frame

(vi) and the depth of the digging tines is independently adjustable in relation to the depth of the seeding tines

(vii) and the digging tines each comprise a knife tine and form a primary passage or trench for the following seeding tines, creating drainage, removing compaction and aerating the soil in use.”

Mzuri alleged that the 576 Patent lacked inventive step over the Claydon PCT application and US5,161,472.

The judge was not persuaded that 576 was obvious over US5,161,472. The skilled person would have been driven to make the particular changes proposed by Mzuri only if the destination of a drill within claim 1 had been in his or her mind.

(1) The date of the decision for the purposes of CPR r 52.12 is the date of the hearing at which the decision is given, which may be ex tempore or by the formal hand down of a reserved judgment: see Sayers v Clarke and Owusu v Jackson. We call this the decision hearing.

(2) A party who wishes to apply to the lower court for permission to appeal should normally do so at the decision hearing itself. In the case of a formal hand down where counsel have been excused from attendance that can be done by applying in writing prior to the hearing. The judge will usually be able to give his or her decision at the hearing, but there may be occasions where further submissions and/or time for reflection are required, in which case the permission decision may post-date the decision hearing.

(3) If a party is not ready to make an application at the decision hearing it is necessary to ask for the hearing to be formally adjourned in order to give them more time to do so: see Jackson v Marina Homes. The judge, if he or she agrees to the adjournment, will no doubt set a timetable for written submissions and will normally decide the question on the papers without the need for a further hearing. As long as the decision hearing has been formally adjourned, any such application can be treated as having been made 'at' it for the purpose of CPR r 52.3(2)(a). We wish to say, however, that we do not believe that such adjournments should in the generality of cases be necessary. Where a reserved judgment has been pre-circulated in draft in sufficient time parties should normally be in a position to decide prior to the hand down hearing whether they wish to seek permission to appeal, and to formulate grounds and such supporting submissions as may be necessary; and that will often be so even where there has been an ex tempore judgment. Putting off the application will increase delay and create a risk of procedural complications. But we accept that it will nevertheless sometimes be justified.

(4) If no permission application is made at the original decision hearing, and there has been no adjournment, the lower court is no longer seized of the matter and cannot consider any retrospective application for permission to appeal: see Lisle-Mainwaring.

(5) Whenever a party seeks an adjournment of the decision hearing as per (3) above they should also seek an extension of time for filing the appellant's notice, otherwise they risk running out of time before the permission decision is made. The 21 days continue to run from the decision date, and an adjournment of the decision hearing does not automatically extend time: see Hysaj. It is worth noting that an application by a party for more time to make a permission application is not the only situation where an extension of time for filing the appellant's notice may be required. It will be required in any situation where a permission decision is not made at the decision hearing. In particular, it may be that the judge wants more time to consider (see para (2) above): unless it is clear that he or she will give their decision comfortably within the 21 days an extension will be required so as to ensure that time does not expire before they have done so. In such a case it is important that the judge, as well as the parties, is alert to the problem."

Comments