Patents - Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd v Bayer Healthcare LLC

Jane Lambert

Patents Court (Mr Justice Mellor) Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd and another Bayer Healthcare LLC [2021] EWHC 2690 (Pat) (8 Oct 2021)

This was an action for the revocation of EP (UK) 2,305,255 under s.72 (1) (a) of the Patents Act 1977:

(a) the invention is not a patentable invention;"

An invention is not patentable unless it satisfies the requirements of s.1 (1) of the Patents Act 1977. Two of those requirements are novelty and involving an inventive step.

The Issues

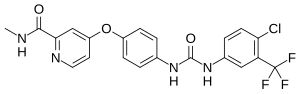

Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. and its British subsidiary, Teva UK Limited, ("Teva") brought these proceedings to clear the way to market a cancer treatment that would have infringed the patent. The action came on for trial before Mr Justice Mellor between 4 and 7 May 2021. According to para [3] of his judgment, Teva had alleged that the patent was invalid for want of novelty as well as want of an inventive step (see Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd and another v Bayer Healthcare LLC [2021] EWHC 2690 (Pat) (8 Oct 2021). As the case developed, Teva relied only on the want of an inventive step and, eventually, only on alleged obviousness over an article entitled "Discovery of a novel Raf kinase inhibitor" by John F Lyons and Others.

Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. and its British subsidiary, Teva UK Limited, ("Teva") brought these proceedings to clear the way to market a cancer treatment that would have infringed the patent. The action came on for trial before Mr Justice Mellor between 4 and 7 May 2021. According to para [3] of his judgment, Teva had alleged that the patent was invalid for want of novelty as well as want of an inventive step (see Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd and another v Bayer Healthcare LLC [2021] EWHC 2690 (Pat) (8 Oct 2021). As the case developed, Teva relied only on the want of an inventive step and, eventually, only on alleged obviousness over an article entitled "Discovery of a novel Raf kinase inhibitor" by John F Lyons and Others.

Inventive Step

S.3 of the Patents Act 1977 provides that an invention shall be taken to involve an inventive step if it is not obvious to a person skilled in the art, having regard to any matter which forms part of the state of the art by virtue only of s. 2 (2) above (and disregarding s.2 (3) above). The state of the art in the case of an invention shall be taken by s.2 (2) to comprise all matter (whether a product, a process, information about either, or anything else) which has at any time before the priority date of that invention been made available to the public (whether in the UK or elsewhere) by written or oral description, by use or in any other way.

S.3 of the Patents Act 1977 provides that an invention shall be taken to involve an inventive step if it is not obvious to a person skilled in the art, having regard to any matter which forms part of the state of the art by virtue only of s. 2 (2) above (and disregarding s.2 (3) above). The state of the art in the case of an invention shall be taken by s.2 (2) to comprise all matter (whether a product, a process, information about either, or anything else) which has at any time before the priority date of that invention been made available to the public (whether in the UK or elsewhere) by written or oral description, by use or in any other way.

Skilled Addressees

There does not seem to have been any dispute that the patent was addressed to a team consisting of a skilled formulator and medicinal chemists.

The Applicable Legal Principles

Mr Justice Mellor directed himself as follows in respect of the applicable legal principles in relation to obviousness at para [101] of his judgment:

"This is familiar territory, but it is nonetheless useful for me to remind myself of the applicable principles which I can take from the Judgment of Arnold J (as he then was) in Allergan Inc. and another v. Aspire Pharma Ltd [2019] EWHC 1085 (Pat) where he described "the overall tenor" of the Supreme Court's judgment as "confirm[ing] the approach which had previously been adopted by the courts to this question". Arnold J. went onto to distil five points from that Judgment, at his [97]-[102]:

'[97]. First, at [60] and [93]-[96] Lord Hodge endorsed, while not mandating, the use of the structured approach set out in Windsurfing International Inc v Tabur Marine (Great Britain) Ltd [1985] RPC 59 as reformulated in Pozzoli SPA v BDMO SA [2007] EWCA Civ 588, [2007] FSR 37 at [33].

[98]. Secondly, at [63] Lord Hodge endorsed, while emphasising that it was not exhaustive, the statement of Kitchin J (as he then was) in Generics (UK) Ltd v H Lundbeck A/S [2007] EWHC 1040 (Pat), [2007] RPC 32 at [72]:

"The question of obviousness must be considered on the facts of each case. The court must consider the weight to be attached to any particular factor in the light of all the relevant circumstances. These may include such matters as the motive to find a solution to the problem the patent addresses, the number and extent of the possible avenues of research, the effort involved in pursuing them and the expectation of success."

[99] Thirdly, at [65] Lord Hodge agreed that it was relevant to consider whether something was "obvious to try", saying that "[i]n many cases the consideration that there is a likelihood of success which is sufficient to warrant an actual trial is an important pointer to obviousness". He nevertheless endorsed the observation of Birss J at first instance that "some experiments which are undertaken without any particular expectation as to result are obvious".

[100] Fourthly, at [69] Lord Hodge said that "the existence of alternative or multiple paths of research will often be an indicator that the invention ... was not obvious", but nevertheless endorsed the statement of Laddie J in Brugger v Medic-Aid Ltd (No 2) [1996] RPC 645 at 661: "[I]f a particular route is an obvious one to take or try, it is not rendered any less obvious from a technical point of view merely because there are a number, and perhaps a large number, of other obvious routes as well."

[101]. Although Lord Hodge did not explicitly make the point, it is implicit in his endorsement of this statement that it remains the law that what matters is whether the claimed invention is obvious from a technical point of view, not whether it would be commercially obvious to implement it.

[102]. Fifthly, at [70] Lord Hodge confirmed that the motive of the skilled person was a relevant consideration. As he put it:

"The notional skilled person is not assumed to undertake technical trials for the sake of doing so but rather because he or she has some end in mind. It is not sufficient that a skilled person could undertake a particular trial; one may wish to ask whether in the circumstances he or she would be motivated to do so. The absence of a motive to take the allegedly inventive step makes an argument of obviousness more difficult.'"

"This is familiar territory, but it is nonetheless useful for me to remind myself of the applicable principles which I can take from the Judgment of Arnold J (as he then was) in Allergan Inc. and another v. Aspire Pharma Ltd [2019] EWHC 1085 (Pat) where he described "the overall tenor" of the Supreme Court's judgment as "confirm[ing] the approach which had previously been adopted by the courts to this question". Arnold J. went onto to distil five points from that Judgment, at his [97]-[102]:

'[97]. First, at [60] and [93]-[96] Lord Hodge endorsed, while not mandating, the use of the structured approach set out in Windsurfing International Inc v Tabur Marine (Great Britain) Ltd [1985] RPC 59 as reformulated in Pozzoli SPA v BDMO SA [2007] EWCA Civ 588, [2007] FSR 37 at [33].

[98]. Secondly, at [63] Lord Hodge endorsed, while emphasising that it was not exhaustive, the statement of Kitchin J (as he then was) in Generics (UK) Ltd v H Lundbeck A/S [2007] EWHC 1040 (Pat), [2007] RPC 32 at [72]:

"The question of obviousness must be considered on the facts of each case. The court must consider the weight to be attached to any particular factor in the light of all the relevant circumstances. These may include such matters as the motive to find a solution to the problem the patent addresses, the number and extent of the possible avenues of research, the effort involved in pursuing them and the expectation of success."

[99] Thirdly, at [65] Lord Hodge agreed that it was relevant to consider whether something was "obvious to try", saying that "[i]n many cases the consideration that there is a likelihood of success which is sufficient to warrant an actual trial is an important pointer to obviousness". He nevertheless endorsed the observation of Birss J at first instance that "some experiments which are undertaken without any particular expectation as to result are obvious".

[100] Fourthly, at [69] Lord Hodge said that "the existence of alternative or multiple paths of research will often be an indicator that the invention ... was not obvious", but nevertheless endorsed the statement of Laddie J in Brugger v Medic-Aid Ltd (No 2) [1996] RPC 645 at 661: "[I]f a particular route is an obvious one to take or try, it is not rendered any less obvious from a technical point of view merely because there are a number, and perhaps a large number, of other obvious routes as well."

[101]. Although Lord Hodge did not explicitly make the point, it is implicit in his endorsement of this statement that it remains the law that what matters is whether the claimed invention is obvious from a technical point of view, not whether it would be commercially obvious to implement it.

[102]. Fifthly, at [70] Lord Hodge confirmed that the motive of the skilled person was a relevant consideration. As he put it:

"The notional skilled person is not assumed to undertake technical trials for the sake of doing so but rather because he or she has some end in mind. It is not sufficient that a skilled person could undertake a particular trial; one may wish to ask whether in the circumstances he or she would be motivated to do so. The absence of a motive to take the allegedly inventive step makes an argument of obviousness more difficult.'"

Applying the Principles

As I have already noted, the main item of prior art upon which Teva relied was the article by John Lyons mentioned above. The learned judge summarized its contents between para [117] and para [126]. He listed the steps the skilled addressees would taken after reading Lyons in [127]. By following that process the skilled formulator and the medicinal chemists would have arrived at the invention.

Further Information

Anyomne wishing to discuss this article may call me on 020 7404 5252 during office hours or send me a message through my contract form.

Comments