Patents - Philip Morris Products v Nicoventures

Patents Court (HH Judge Hacon) Philip Morris Products SA and another v Nicoventures Trading Ltd and another [2023] EWHC 2616 (Pat) (25 Oct 2023)

This was a claim by Philip Morris Products SA and Philip Morris Limited ("PMI") for the revocation of European patent (UK) 3 367 830 B1 ("EP830") and a counterclaim by Nicoventures Trading Limited and British American Tobacco (Investments) Limited ("BAT") for the infringement of that patent. There was also an application by BAT to amend the patent and an application by PMI for an Arrow declaration. These proceedings came on for trial before His Honour Judge Hacon sitting as a judge of the High Court between 21 and 23 and on 27 and 28 Sept, 2023. The learned judge delivered judgment on 25 Ocr 2023 (see Philip Morris Products SA and another v Nicoventures Trading Ltd and another [2023] EWHC 2616 (Pat) (25 Oct 2023)). By para [216] of his judgment he dismissed the counterclaim. The patent had not been anticipated but it was obvious over the prior art. He denied permission to amend because it would not save the patent and would actually constitute added matter. He refused an Arrow declaration because PMI could not explain why they needed one,.

The Patent

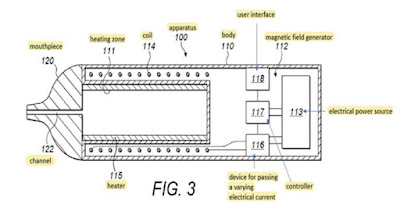

The patent was granted for an "Article for use with apparatus for heating smokable material." The following abstract describes it by reference to these drawings:

"Disclosed is an article (1) for use with apparatus (100) for heating smokable material to volatilise at least one component of the smokable material. The article (1) comprises smokable material (10), such as tobacco, and a heater (20) for heating the smokable material (10). The heater (20) comprises heating material that is heatable by penetration with a varying magnetic field. The heating material has a Curie point temperature that is less than the combustion temperature of the smokable material (10)."

To understand the abstract it is necessary to understand the term "Curie point". The judge explained at para [43] of his judgment that the "Curie point" is the temperature at which materials with permanent magnetic properties lose those properties. Earlier he explained that in an electronic cigarette tobacco compounds are heated, vaporized and inhaled rather than burnt. The generic name of the technology is "heat not burn" or "HNB".

Later he added:

In some HNB products heat is generated by chemicals. In others, an electrical heater is used of which there are two kinds known respectively as resistive and inductive. In a resistive heater, an electric current passes through resistant material so that some of the electrical energy is converted into heat. Inductive heaters rely on the application of an oscillating magnetic field to an electrically conducting material known as the susceptor. This field is created by applying an alternating electric current to a coil of a conductor placed close to the susceptor. Eddy currents generated in the susceptor cause the heating.

"(1) A system, comprising:

(2) Apparatus (100) for heating smokable material comprising tobacco to volatilise at least one component of the smokable material; and

(3) an article for use with the apparatus, wherein the article comprises smokable material;

(4) wherein the apparatus comprises: a heating zone (111) for receiving the article,

(5) a heater (115) for heating the smokable material when the article is in the heating zone,

(6) wherein the heater extends to opposite longitudinal ends of the mass of smokable material and is formed of heating material that is heatable by penetration with a varying magnetic field, and

(7) a magnetic field generator (112) for generating a varying magnetic field that penetrates the heating material;

(8) characterised in that a maximum temperature to which the heater is heatable by penetration with the varying magnetic field in use is exclusively determined by a Curie point temperature of the heating material that comprises an alloy comprising iron and nickel; and

(9) wherein the magnetic field generator comprises an electrical power source, a coil, a device for passing a varying electrical current through the coil, a controller, and a user interface for user-operation of the controller, wherein the coil is a helical coil of electrically-conductive material."

The judge considered the counterclaim first. BAT alleged that PMI had infringed its patent by marketing an HNB product called the IQOS ILUMA. The judge described that product as having two parts:

- a device that generates an alternating magnetic field with an induction coil, rechargeable batteries, associated electronics and user interface and

- a second part, insertable into the device, called the "stick" which is a consumable containing tobacco, glycerin, a heater, a filter and a mouthpiece filter.

Turning to whether the IQOS ILUMA infringed as an equivalent the learned judge identified the variant as an HNB system where (a) the heater is in the consumable and (b) the maximum temperature of the heater is not at all times fixed by reference to a Curie point of the heating material. He then asked each of the modified Improver questions in relation to that variant and concluded that it did not fall within any of the claims of the patent in suit.

- A thread of posts with the subject head "Induction Vaporizer (based on 'Curie' alloys)" dated on or before 2 December 2011 by several individuals including one posting under the pseudonym "Egzoset" on the Fuck Combustion online forum ("Egzoset"); and

- PCT Application No. WO 2014/023965 A1 ("Duffield").

"[113]...... it is long established that to anticipate an invention the prior publication must contain "clear and unmistakable directions to do what the patentee claims to have invented", see General Tire & Rubber Co v Firestone Tyre & Rubber Co Ltd [1972] RPC 457, at 444. The same passage of the judgment of the Court of Appeal in General Tire put the test of anticipation in this way (at 444):

'… if carrying out the directions contained in the prior inventor's publication will inevitably result in something being made or done which, if the patentee's patent were valid, would constitute an infringement of the patentee's claim, this circumstance demonstrates that the patentee's claim has in fact been anticipated.'

[114] The relevant passage from General Tire was more fully quoted (there seems to have been a typo regarding the page reference) and approved by Lord Hoffman in SmithKline Beecham plc's (Paroxetine Methanesulfonate) Patent [2005] UKHL 59, at [21]. Lord Hoffmann continued:

'… the matter relied upon as prior art must disclose subject-matter which, if performed, would necessarily result in infringement of the patent.'"

"(1) (a) Identify the notional 'person skilled in the art';

(b) Identify the relevant common general knowledge of that person;

(2) Identify the inventive concept of the claim in question or if that cannot readily be done, construe it;

(3) Identify what, if any, differences exist between the matter cited as forming part of the 'state of the art' and the inventive concept of the claim or the claim as construed;

(4) Viewed without any knowledge of the alleged invention as claimed, do those differences constitute steps which would have been obvious to the person skilled in the art or do they require any degree of invention?"

"(1) Whether the skilled person had a preference at the priority date for a resistive heater over an induction heater for HNB products.

(2) Whether the skilled person was aware that induction heating was generated in large part (or at all) by magnetic hysteresis.

(3) Knowledge of certain details of the design of HNB products."

"An HNB system in which (i) an article containing smokeable material is inserted into the heating zone of a heating apparatus, (ii) the smokable material is heated by inductive heating and (iii) the maximum temperature of the heater in the apparatus is exclusively determined by a Curie point of the heating material. 'Exclusively determined' means that the maximum temperature is at all times fixed by reference to a Curie point and dependent on no other factor."

The learned judge set out his reasoning at [145]:

"The key difference between the matter disclosed in Egzoset and that of claim 13 is that claim 13 dispenses with an induction hob as the heater – a system excluded from the scope of claim 13 since, as I have found, the maximum temperature of the heater is not determined by the Curie point of the heating material when a commercial induction hob is used. The obvious way for the skilled team to go – in fact a good deal more obvious than using an induction hob – was to structure the product in a manner something like that of the HNB tobacco products of the prior art, see for example the PMI Accord or IQOS system illustrated above, but using an inductive heater. Mr Wensley accepted as much in cross-examination. A product in that sort of form was what the market wanted. No difficulty in making such a thing was identified in the evidence such that it would have prevented or discouraged the skilled team from creating such a product. It would have been a system within claim 13."

"The refill unit contains the volatile liquid and a susceptor. It is placed into the main unit which is fitted with an induction coil. Power is supplied to the coil which then applies a magnetic field to the susceptor. The susceptor heats, primarily by magnetic hysteresis, causing the volatile liquid to evaporate through perforation holes created by piercing devices in the lid of the main unit. "

"To provide the device with a stable maximum operating temperature the susceptor(s), may comprise a material with a stable Curie temperature, preferably less than 150°C. When the magnetic susceptor(s) is heated beyond this temperature, the susceptor(s) will become paramagnetic and no longer be susceptible to hysteresis heating until such time it cools down back below its Curie temperature. By selecting a magnetic susceptor(s) with a low and stable Curie temperature, it is possible to prevent the temperature of the volatile liquid in the volatile material transport means exceeding a predetermined level, even if for some reason excess power is supplied to the induction coil."

"[8] The issue of added matter falls to be determined by reference to a comparison of the application for the patent as filed and the granted patent. As Aldous L.J. said in Bonzel v Intervention Ltd (No 3) [1991] R.P.C. 553 at p.574:

'The task of the Court is threefold:

(1) To ascertain through the eyes of the skilled addressee what is disclosed, both explicitly and implicitly in the application.

(2) To do the same in respect of the patent as granted.

(3) To compare the two disclosures and decide whether any subject matter relevant to the invention has been added whether by deletion or addition. The comparison is strict in the sense that subject matter will be added unless such matter is clearly and unambiguously disclosed in the application either explicitly or implicitly.'

'I think the test of added matter is whether a skilled man would, upon looking at the amended specification, learn anything about the invention which he could not learn from the unamended specification.'"

Arrow Declarations

"A heat-not-burn system consisting of a heating device and single-use tobacco-containing sticks:

1. The device comprises:

a. a helical coil module, which generates an alternating magnetic field, the module surrounding a cavity at the mouth end of the device into which the stick is inserted;

b. control electronics and a microcontroller;

c. a rechargeable battery, which supplies power for the electronics and helical coil module; and

d. user interface components, such as a user-operated switch.

2. The sticks are elongate and cylindrical and include:

a. a tobacco plug, which comprises homogenised tobacco material and glycerin, and a metallic susceptor that is surrounded by and in contact with the tobacco material; and

b. a mouthpiece filter at the proximal end of the stick.

3. The tobacco plug is wrapped in a plug wrapper made of paper. The tobacco plug is further wrapped by an outer paper wrapper. Both the plug wrapper and the outer paper wrapper are wrapped in such a way that the longitudinal edges of the wrapper overlap, and an adhesive is applied to one of the longitudinal edges of the wrapper so that when edges overlap, they are glued together.

4. The metallic susceptor in the stick is a flat strip that is impermeable to air. The susceptor comprises metallic material that is electrically conductive and magnetic. The susceptor is uniform in shape and has a substantially rectangular cross-section perpendicular to its length. The susceptor is approximately 4mm in width, less than 0.6 mm thick and approximately 12 mm long. The susceptor extends longitudinally from one end of the tobacco plug to the opposite end of the tobacco plug and is positioned within the tobacco plug such that it is not in contact with the plug wrapper (or outer paper wrapper).

5. To use the system, the stick is inserted into the cavity at the mouth end of the device. When the user turns the device on using the user-operated switch, the helical coil module is activated, generating an alternating magnetic field that causes the susceptor in the stick to heat up. The device heats, but does not burn, tobacco in the sticks to generate a nicotine-containing aerosol that is inhaled by the user when the user draws on the mouthpiece filter of the stick."

(1) PCT Application No. WO2015/177294 A1 ("Mironov") claiming a priority date of 21 May 2014; and

(2) Chinese Utility Model No. CN204519365U ("Wu") which has an application date 7 Feb 2015.

Judge Hacon discerned the following principles from Fujifilm Kyowa Kirin Biologics Co., Ltd v Abbvie Biotechnology Ltd [2017] EWCA 1, Glaxo Group Ltd v Vectura Ltd [2018] EWCA Civ 1496 and Mexichem UK Ltd v Honeywell International Inc [2020] EWCA Civ 473:

"(1) The court has a broad and flexible discretion to grant Arrow declaratory relief, Mexichem at [13].

(2) The circumstances in which an Arrow declaration will be justified are likely to be uncommon, Fujifilm at [95].

(3) The discretion should be exercised only where the declaration will serve a useful purpose, which requires critical examination by the court, Glaxo at [25]; Mexichem at [13].

(4) The requirement of a useful purpose will not be fulfilled solely because the respondent has pending patent applications and the applicant would like to know whether it will infringe any patents which may be granted pursuant to those applications, Fujifilm at [93] and [94(iv)) and (v)]; Glaxo at [25].

(5) The usual course envisaged by the statute is that the applicant should wait and see what, if any, patents are granted and where necessary use the remedy of revocation, Fujifilm at [93].

(6) Where it appears that the statutory remedy of revocation is being frustrated by shielding the subject-matter from scrutiny by the national court, this may be a reason for the court to intervene with a declaration, Fujifilm at [93].

(7) The court must guard against the application being used as a disguised attack on the validity of a granted patent, Fujifilm at [81]-[82] and [98(ii)].

(8) A declaration may be sought in relation to one or more features of a product or process, as opposed to a product or process in its entirety, Mexichem at [18]-[20].

(9) Where a declaration is sought in respect of only one feature or some features of a product or process, the level of generality of the proposed declaration may be relevant to whether it serves a useful purpose, Mexichem at [18].

(10) The court may take into account the possibility that a declaration is likely to be useful solely in arguments on obviousness in which it is deployed in an illegitimate step-by-step analysis of obviousness, although it may be difficult to know that this is likely to arise, Mexichem [22]-[25].

(11) The features in respect of which the declaration is sought must be defined with sufficient clarity, Glaxo at [30].

(12) Equally, the useful purpose said to justify the declaration must be clearly identified, Mexichem at [13]."

"(13) Subject always to the qualifications referred to in (7), (11) and (12) above, an Arrow declaration is likely to serve a useful purpose if the applicant can show that (a) the respondent's portfolio of patent applications and/or patents creates real doubt, likely to continue for a significant period, as to whether technical subject-matter which the applicant wishes to exploit can lawfully be used, (b) the applicant's reasonable intention to exploit that subject-matter would be of significant commercial advantage to it and (c) the declaration sought would, if granted, eliminate or significantly reduce the delay.

Policy on Arrow Statements

"I do not believe that it would be a good idea to encourage litigants to fill the court diary with applications for Arrow declarations confident in the knowledge that provided the application overcomes any attempt to strike it out, it is bound to lead to a finding on the issue which the applicant would like the court to address irrespective of whether in the circumstances the court's discretion should be exercised to grant a declaration. The important issues arising on discretion would be sidelined."

"Arrow declarations are an important remedy but they are available in relatively rare circumstances. They are discretionary and hence almost entirely dependent on their own facts."

.

Anyone requiring further information about them may call me on 020 7404 5252 during office hours or send me a message through my contact form.

Comments