Patents - Alcon Eye Care UK v AMO Development, LLC

Business and Property Courts of England and Wales, Intellectual Property, Patents Court (Mr Justice Mellor) Alcon Eye Care UK v AMO Development, LLC [2022] EWHC 955 (Pat) (26 April 2022)

This was a claim by Alcon Eye Care UK Limited and Alcon Inc ("Alcon") for the revocation of European patent (UK) 1 835 861 B2 ("EP861") for “Apparatus for Patterned Plasma-mediated Laser Trephination of the Lens Capsule” and European Patent (UK) 2 548 528 B1 ("EP528"), entitled “Apparatus for Patterned Plasma-mediated Laser Trephination of the Lens Capsule and Three-dimensional Phaco-Segmentation”. The owner of those patents, AMO Development LLC ("AMO"). AMO counterclaimed for infringement of its patents by LenSx laser surgery system. It was common ground that if the patents were valid they would have been infringed by that system. The action and counterclaim came on for trial before Mr Justice Mellor between 26 Oct and 5 Nov 2021. His lordship delivered judgment on 26 April 2022 (see Alcon Eye Care UK Ltd, v AMO Development, LLC [2022] EWHC 955 (Pat) (26 April 2022)), By para [510] of his judgment. he found both patents to be invalid primarily for obviousness but also for insufficiency.

The Inventions

Both patents were for ophthalmic surgical systems for carrying out cataract surgery. EP528 is a divisional of EP861. Both claimed a system comprising a laser and an imaging device for carrying out a surgical procedure on the eye. The primary difference between them lay in their specific applications:

- the claims of EP861 were for a device for performing an anterior capsulotomy (AC) (i.e. cutting the anterior lens capsule); and

- the claims of EP528 were for a device for cutting the lens cortex and nucleus into fragments - lens fragmentation (LF).

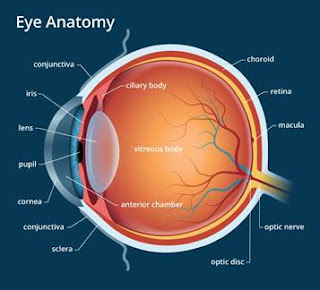

According to the judge an understanding of

(a) the structure of the eye;

(b) the state of the art surgical procedures on the eye, including in particular, the procedures within cataract surgery of performing an anterior capsulotomy and lens fragmentation and removal, but also other procedures such as radial keratotomy;

(c) the use of lasers in such surgical procedures and

(d) imaging techniques suitable for use on tissues in the eye, including in particular OCT and confocal microscopy.

was essential for understanding both the patents in suit and this litigation. The technical background was discussed between paras [10] and [137] of the judgment. No attempt is summarize or explain it in this short case note.

Grounds of Invalidity

Two of the grounds on which a patent may be revoked are:

- the invention is not a patentable one; and

- the specification of the patent does not disclose the invention clearly enough and completely enough for it to be performed by a person skilled in the art

S.1 (1) of the Act provides that a patent may be granted for an invention only if a number of conditions are satisfied. One of these conditions is that the patent involves an inventive step. S.3 states that an invention shall be taken to involve an inventive step if it is not obvious to a person skilled in the art, having regard to any matter which forms part of the state of the art. For these purposes "the state of the art" means "all matter (whether a product, a process, information about either, or anything else) which has at any time before the priority date of that invention been made available to the public (whether in the United Kingdom or elsewhere) by written or oral description, by use or in any other way,"

At para [6] of his judgment, Mr Justice Mellor said that the live issues at trial were obviousness over prior art that he referred to as Freedman and Mühlhoff and almost nothing was said about insufficiency.

Obviousness

The judge noted that the correct approach as to obviousness was set out by Lord Hodge between paras [52] and [73] of his judgment in Actavis Group PTC EHF and others v ICOS Corporation and another [2019] Bus LR 1318, [2019] UKSC 15, (2019) 167 BMLR 1, [2019] RPC 9, [2020] 1 All ER 213. Although Mr Justice Mellor did not do so it is worth quoting para [60] of Lord Hodge's judgment as the judge applied the following methodology:

"In addressing the statutory question of obviousness in section 3 of the 1977 Act it is common for English courts to adopt the so-called Windsurfing/Pozzoli structure which asks these questions:

(1) (a) Identify the notional ‘person skilled in the art’;

(b) Identify the relevant common general knowledge of that person;

(2) Identify the inventive concept of the claim in question or if that cannot readily be done, construe it;

(3) Identify what, if any, differences exist between the matter cited as forming part of the ‘state of the art’ and the inventive concept of the claim or the claim as construed;

(4) Viewed without any knowledge of the alleged invention as claimed, do those differences constitute steps which would have been obvious to the person skilled in the art or do they require any degree of invention?”

(Pozzoli SPA v BDMO SA [2007] EWCA Civ 588; [2007] FSR 37, para 23 per Jacob LJ). The fourth question is the statutory question and the first three questions or tasks, the second and third of which involve knowledge and consideration of the invention, are a means of disciplining the court’s approach to that fourth question: DSM NV’s Patent [2001] RPC 35, para 55 per Neuberger J; Actavis UK Ltd v Novartis AG [2010] EWCA Civ 82; [2010] FSR 18, para 21 per Jacob LJ. "

Mr Justice Mellor also referred to para [61] of Lord Justice Floyd's judgment in Koninklijke Philips N.V. v Asustek Computer Incorporation and others [2019] EWCA Civ 2230, [2020] RPC 1:

"The task for the party attacking the patent on the ground of obviousness is to show how the skilled person would arrive at the invention claimed from the disclosure of the prior art. If the invention claimed is, as it is here, a simple idea, then it is correct that this simple idea is the target for the obviousness attack. That does not mean, however, that the court is entitled to assume that the skilled person takes a different approach to the prior art, stripping out from it detail which the skilled person would otherwise have taken into account, or ignoring paths down which the skilled person would probably be led: see the passage from Pozzoli cited above. The nature of the invention claimed cannot logically impact on the way in which the skilled person approaches the prior art, given that the prior art is to be considered without the benefit of hindsight knowledge of the invention."

Step I (a): Identifying the Skilled Addressee

The first step of the Windsurfing/Pozzoli analysis is to identify the skilled addressee. The parties agreed that they would be a team including a skilled ophthalmologist ("SO") and a skilled engineer ("SE") but they could not agree on the characteristics of those members of that team or their common general knowledge ("CGK") which in turn fed into major differences of interpretation of each piece of the prior art. To resolve their differences the judge reminded himself of Mr Justice Henry Carr's principles on identifying the skilled team and the CGK in Garmin (Europe) Limited v Koninklijke Philips N.V. [2019] EWHC 107 (Pat) at [85]:

"i) A patent specification is addressed to those likely to have a real and practical interest in the subject matter of the invention (which includes making it as well as putting it into practice).ii) The relevant person or persons must have skill in the art with which the invention described in the patent is concerned. As Aldous LJ stated in Richardson Vicks Inc's Patent [1997] RPC 888 at 895:

'Each case will depend upon the description in the patent, but there is no basis in law or logic for including within the concept of "a person skilled in the art", somebody who is not a person directly involved in producing the product described in the patent or in carrying out the process of production.'

iii) The skilled addressee has practical knowledge and experience of the field in which the invention is intended to be applied. He/she (hereafter "he") reads the specification with the common general knowledge of persons skilled in the relevant art, and reads it knowing that its purpose is to disclose and claim an invention.

iv) A patent may be addressed to a team of people with different skills. Each such addressee is unimaginative and has no inventive capacity.

v) Although the skilled person/team is a hypothetical construct, its composition and mind-set is founded in reality. As Jacob LJ said in Schlumberger at [42]:

' ... The combined skills (and mindsets) of real research teams in the art is what matters when one is constructing the notional research team to whom the invention must be obvious if the patent is to be found invalid on this ground.'"

4. Mr Waugh QC argues that since the specification enables a wider class of persons - organometallic chemists - to put the invention into effect, then that class of persons is the relevant class. I do not think this follows. After all, obviously the patent is in principle of interest to anybody, whether or not an organometallic chemist, who wishes to enter the field. That fact cannot be relevant to identifying the skilled addressee. It is not legitimate to draw the class of addressee so wide that the specific knowledge and prejudices of those most closely involved in the actual field with which the patent is concerned do not form part of the prejudices and attributes of the skilled person."

"[73] As the judge explained, in this case there was a dispute as to the identity of the team to whom the patent is addressed. MedImmune contended it is addressed to a team consisting of an immunologist and a molecular biologist, perhaps assisted by a chemist. Novartis argued the patent is addressed to a team of scientists with differing backgrounds in areas such as immunology, in particular antibody structural biology, molecular biology and protein chemistry, but with a common interest in antibody engineering. As the judge identified, the essential difference between the two formulations lies in the degree of specialisation of the team in the field of antibody engineering.

[74] The judge preferred Novartis' submission on the basis that the evidence showed that real research teams in the field were teams of the kind contended for by Novartis. He added that, in his view, the specification of the patent is consistent with this characterisation of the skilled team.

[75] MedImmune contended that the judge fell into error in so finding because the invention has a broad application and is not confined to antibody engineering. It continued that expertise in immunology and molecular biology is sufficient to implement its teaching.

[76 ] I have no doubt that the judge identified the skilled team correctly. As Jacob L.J. explained in Schlumberger Holdings Ltd v Electromagnetic Geoservices AS [2010] EWCA Civ 819, [2010] RPC 33 at [42], the court will have regard to the reality of the position at the time and the combined skills of real research teams in the art. A little later, at [53], he continued that where the invention involves the use of more than one skill, if it is obvious to a person skilled in the art of any one of those skills, then the invention is obvious. Finally, at [65], he explained that in the case of obviousness in view of the state of the art, a key question is generally "what problem was the patentee trying to solve?" That leads one in turn to consider the art in which the problem in fact lay. It is the notional team in that art which is the relevant team making up the person skilled in the art."

Mr Justice Mellor reminded himself of Mr Justice Arnold's conservation in KCI v Smith & Nephew [2010] EWHC 1487 at [104]-[112] that to be CGK, information must be generally known to the bulk of those in the art, and generally accepted as a good basis for further action. He also referred to para [24] of Mr Justice Birss's judgment in Merck v Ono [2015] EWHC 2973 (Pat)L

"I do not believe the court in General Tire was seeking to address factual circumstances like those said to arise in this case. In principle the common general knowledge of a skilled person must be capable of including contradictory ideas on a topic, always assuming that information reaches the standard for common general knowledge. The existence of a defined area of doubt and uncertainty does not mean that, in principle, such knowledge is not part of the common general knowledge. An example, referred to by Ono, was in the judgment of Floyd J in Regeneron v Genentech [2012] EWHC 657 (Pat) e.g. at paragraph 67 and the conclusion at paragraph 88 (upheld by the Court of Appeal at [2013] EWCA Civ 93, paragraph 22). Merck submitted the evidence in Regeneron was much stronger than the evidence in this case. The submission about evidence does not alter the point of principle."

"[13.[ ….it is important to bear in mind the warning of Aldous LJ. in Beloit Technologies Inc. v. Valmet Paper Machinery Co. Ltd [1997] RPC 489 at 494, he said this:

'It has never been easy to differentiate between common general knowledge and that which is known by some. It has become particularly difficult with the modern ability to circulate and retrieve information. Employees of some companies, with the use of libraries and patent departments, will become aware of information soon after it is published in a whole variety of documents; whereas others, without such advantages, may never do so until that information is accepted generally and put into practice. The notional skilled addressee is the ordinary man who may not have the advantages that some employees of large companies may have. The information in a patent specification is addressed to such a man and must contain sufficient details for him to understand and to apply the invention. It will only lack an inventive step if it is obvious to such a man.'

It follows that evidence that a fact is known or event well-known to a witness does not establish that that fact forms part of the common general knowledge. Neither does it follow that it will form part of the common general knowledge if it is recorded in a document.

[14]. Aldous L.J. said that in order to establish whether something is common general knowledge, the first and most important step is to look at the sources from which the skilled addressee could acquire his information." I would add that although it has to be remembered that a specification may fail to provide sufficient details for the addressee to understand and apply the invention, and so be insufficient and invalid, it is often possible to deduce the attributes which the skilled man must possess from the assumptions which the specification clearly makes about his abilities.’

"An ophthalmic surgical system for creating surgical cuts in an eye having a lens capsule and a lens nucleus within the lens capsule; the system comprising:

a laser source (10, LS) configured to deliver a laser beam (11) comprising a plurality of laser pulses;

an optical coherence tomography (OCT) device configured to generate an image of the eye tissue from which the lens capsule and the lens nucleus of the eye tissue can be identified;

a delivery system for focusing the laser beam (11) onto the eye tissue, the delivery system including one or more movable optical elements, the delivery system operable to focus the laser beam at a focal point within the eye and control the location of the focal point to create cuts within the lens cortex and the lens nucleus; and

a controller (12, CPU) operatively coupled with the optical coherence tomography (OCT) device, the laser source and the delivery system and configured to determine parameters including upper and lower axial limits of the focal planes for cutting the lens capsule and segmentation of the lens cortex and lens nucleus based on the generated image of the eye tissue and to control the delivery system to scan the laser beam such that the focal point of the laser beam is scanned in a pattern at multiple depths within the lens cortex and the lens nucleus to segment the lens cortex and the lens nucleus into fragments."

The system of claim 1, wherein the controller is configured to control the delivery system to segment the lens cortex and the lens nucleus into the fragments by scanning the focal point within the lens nucleus in one or more scanning patterns so as to create cuts that separate the fragments."

"an ophthalmic surgical system for performing an anterior capsulotomy, comprising

(1) a pulsed laser light source for generating a light beam configured to produce dielectric breakdown within the eye tissue at its focal point,

(2) an OCT or confocal microscopy imaging device for generating an image of the eye tissue,

(3) a delivery system for focussing the light beam onto the eye tissue and deflecting it in a pattern,

each of which is operatively coupled to

(4) controlling means configured

a) to operate the imaging device to scan the eye tissue to generate imaging data for the anterior portion of the lens,

b) to use the imaging data to determine parameters of a cutting pattern for performing an anterior capsulotomy, and

c) to operate the light source and the delivery system to scan the light beam in the cutting pattern with its focal point being guided by the controlling means based on the imaging data to perform the anterior capsulotomy."

"An ophthalmic surgical system for creating surgical cuts in an eye having a lens capsule and a lens nucleus within the lens capsule; the system comprising:

a laser source (10, LS) configured to deliver a laser beam (11) comprising a plurality of laser pulses;

an optical coherence tomography (OCT) device configured to generate an image of the eye tissue from which the lens capsule and the lens nucleus of the eye tissue can be identified;

a delivery system for focusing the laser beam (11) onto the eye tissue, the delivery system including one or more movable optical elements, the delivery system operable to focus the laser beam at a focal point within the eye and control the location of the focal point to create cuts within the lens cortex and the lens nucleus; and

a controller (12, CPU) operatively coupled with the optical coherence tomography (OCT) device, the laser source and the delivery system and configured to determine parameters including upper and lower axial limits of the focal planes for cutting the lens capsule and segmentation of the lens cortex and lens nucleus based on the generated image of the eye tissue and to control the delivery system to scan the laser beam such that the focal point of the laser beam is scanned in a pattern at multiple depths within the lens cortex and the lens nucleus to segment the lens cortex and the lens nucleus into fragments."

"The system of claim 2, wherein:

scanning the laser beam within the lens nucleus in one or more scanning patterns comprises sequentially applying laser pulses to the same lateral pattern at different depths within the lens nucleus; and

the laser pulses are first applied to the same lateral pattern at a maximum depth within the lens nucleus and then applied to sequentially shallower depths within the lens nucleus."

The inventive concept of claim 1 of EP528 was summarized as being

"an ophthalmic surgical instrument, comprising

(1) a pulsed laser light source for delivering a laser beam,

(2) an OCT device for generating an image of the eye tissue from which the lens capsule and lens nucleus can be identified, and

(3) a delivery system which is operable to focus the laser beam and control the location of its focal point to create cuts within the cortex and the nucleus,

each of which is operatively coupled to

(4) controlling means configured

a) to determine parameters including upper and lower axial limits of the focal planes for cutting the capsule and segmenting the lens cortex and nucleus based on the generated image of the eye tissue so that

b) the focal point of the laser beam can be scanned in a pattern at multiple depths within the cortex and nucleus to segment them into fragments."

i) The use of his system to perform AC or LF.

ii) A laser which can effect photo-disruption.

Mühlhoff was a PCT application filed by Carl Zeiss Meditec AG on 22 Aug 2003 and published on 1 April 2004. It is entitled "Device and Method for Measuring an Optical Penetration in a Tissue." The judge described it between [395] and [460]. At para [465] he said:

"[465] ........ As for the third step, the differences between Mühlhoff and claim 1 of EP861 and EP528, respectively, are that Mühlhoff does not disclose using its apparatus for AC or LF. AMO submitted there was a further difference: that Mühlhoff does not disclose pre-planning as required by each claim 1. Whether this is a difference or not depends on the starting point and I consider this below.

ii) The prompt to consider use to make ‘incisions in the lens’ was explicit.

iii) The step to use the OCT system to image in advance so that the laser incision occurs in the right place was modest.

The judge added at [478] that:

"This reasoning provides the Skilled Team with systems which land in claim 1 of EP861 and in claim 1 of EP528. I also point out that both Patents are ‘ideas’ patents. By the point reached in paragraph 472 above, the Skilled Team have reached the idea in claim 1 of each Patent. Based on my findings as to the key CGK, these ideas would have been well worth investigating for the Skilled Team."

Anyone wishing to discuss this case can call me on 020 7404 5252 during office hours or send me a message through my contact form.

Comments