Registered Designs - Marks and Spencer Plc v Aldi Stores Ltd.

Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (HH Judge Hacon) Marks and Spencer Plc v Aldo Stores Ltd. [2023]EWHC 178 (IPEC) 31 Jan 2023

This was a claim for the infringement of the following registered designs:

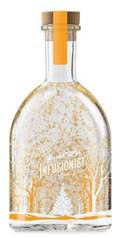

The designs were registered on 29 April 2021 by Marks and Spencer Plc ("M&S"). M&S complained that Aldi Stores Ltd ("Aldi") had infringed those registered designs by marketing and selling gin liqueurs in the following bottles from Nov 2021:

The action came on for trial before His Honour Judge Hacon on 16 Dec 2022 who delivered judgment on 31 Jan 2023. The last of the 5 designs was not pursued. At para [84] of his judgment, the learned judge concluded that the marketing of those gin liqueur products infringed the first 4 registered designs (Marks and Spencer Plc v Aldi Stores Ltd.[2023] EWHC 178 (IPEC)).

Legislation

Judge Hacon noted that the Registered Designs Act 1949 had been amended by The Registered Designs Regulations 2001 (SI 2001/3949) to implement Directive 98/71/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 October 1998 on the legal protection of designs. As such, the Act had to be interpreted in accordance with the principles of EU law as explained by the EU and English courts up to 31 Dec 2020. S.6 of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 requires the English courts to follow any decisions of the Supreme Court or Court of Appeal after 31 Dec 2020 that may be inconsistent with those principles, but they may continue to have regard to the judgments of the Court of Justice of the European Union that have been delivered after that date.

S.7 of the Registered Designs Act 1949 (as amended) provides as follows:

“Right given by registration

(1) The registration of a design under this Act gives the registered proprietor the exclusive right to use the design and any design which does not produce on the informed user a different overall impression.

(2) For the purposes of subsection (1) above and section 7A of this Act any reference to the use of a design includes a reference to—

(a) the making, offering, putting on the market, importing, exporting or using of a product in which the design is incorporated or to which it is applied; or

(b) stocking such a product for those purposes.

(3) In determining for the purposes of subsection (1) above whether a design produces a different overall impression on the informed user, the degree of freedom of the author in creating his design shall be taken into consideration.

(4) The right conferred by subsection (1) above is subject to any limitation attaching to the registration in question (including, in particular, any partial disclaimer or any declaration by the registrar or a court of partial invalidity).”

The judge directed himself at para [8] of his judgment that a design thus infringes a registration if it does not produce on the informed user a different overall impression to that produced by the design as registered.

He added that "the task of the court involves more than a simple comparison of two designs and a judgment reached on that comparison". One difficulty in registered design cases is that the features that are included in a registration are not always clear. For example, in Magmatic Limited v PMS International Group plc [2016] Bus LR 371, [2016] 4 All ER 1027, [2016] WLR(D) 126, [2016] ECDR 15, [2016] RPC 11, [2016] UKSC 12, Lord Neuberger said:

"[30] … It is, of course, up to an applicant as to what features he includes in his design application. He can make an application based on all or any of ‘the lines, contours, colours, shape, texture . . . materials . . . and/or . . . ornamentation’ of ‘the product’ in question. Further, he can make a large number of different applications, particularly as the Principal Regulation itself provides that applications for registration have to be cheap and simple to make. As Lewison J put it in Procter & Gamble Co v Reckitt Benckiser (UK) Ltd. [2006] EWHC 3154 (Ch), [2007] FSR 13, [2007] ECDR 4, para 48:

"[30] … It is, of course, up to an applicant as to what features he includes in his design application. He can make an application based on all or any of ‘the lines, contours, colours, shape, texture . . . materials . . . and/or . . . ornamentation’ of ‘the product’ in question. Further, he can make a large number of different applications, particularly as the Principal Regulation itself provides that applications for registration have to be cheap and simple to make. As Lewison J put it in Procter & Gamble Co v Reckitt Benckiser (UK) Ltd. [2006] EWHC 3154 (Ch), [2007] FSR 13, [2007] ECDR 4, para 48:

'The registration holder is entitled to choose the level of generality at which his design is to be considered. If he chooses too general a level, his design may be invalidated by prior art. If he chooses too specific a level he may not be protected against similar designs.'

So, when it comes to deciding the extent of protection afforded by a particular Community registered design, the question must ultimately depend on the proper interpretation of the registration in issue, and in particular of the images included in that registration.”

In this case, the difficulty was whether one of the features of each of the first four registered designs in suit was an integrated light at the base of the bottle. Each contained the description “Light Up Gin Bottle” but both parties submitted that the description was irrelevant to the interpretation of the designs. The judge remarked that if that was correct there was a real possibility that members of the public consulting the design register could be misled by the description.

Approach when comparing an Accused Design to a Registered Design

The parties agreed that Judge Hacon had set out the approach to be followed when comparing a registered design to an alleged infringement at para [118] of his judgment in Cantel Medical (UK) Limited v ARC Medical Design Limited [2018] EWHC 345 (Pat) which I discussed that judgment in Patents and Designs: Cantel Medical (UK) Ltd v ARC Medical Design Ltd. on 9 March 2018:

“[181] I here adapt the four stages prescribed by the General Court in H&M Hennes for assessing the individual character of a Community design to the comparison of an RCD with an accused design, adding other matters relevant to the present case. The court must:

(1) Decide the sector to which the products in which the designs are intended to be incorporated or to which they are intended to be applied belong;

(2) Identify the informed user and having done so decide (a) the degree of the informed user’s awareness of the prior art and (b) the level of attention paid by the informed user in the comparison, direct if possible, of the designs;

(3) Decide the designer’s degree of freedom in developing his design;

(4) Assess the outcome of the comparison between the RCD and the contested design, taking into account (a) the sector in question, (b) the designer’s degree of freedom, and (c) the overall impressions produced by the designs on the informed user, who will have in mind any earlier design which has been made available to the public."

He added at [182]:

"(5) Features of the designs which are solely dictated by technical function are to be ignored in the comparison.

(6) The informed user may in some cases discriminate between elements of the respective designs, attaching different degrees of importance to similarities or differences. This can depend on the practical significance of the relevant part of the product, the extent to which it would be seen in use, or on other matters.”

"(5) Features of the designs which are solely dictated by technical function are to be ignored in the comparison.

(6) The informed user may in some cases discriminate between elements of the respective designs, attaching different degrees of importance to similarities or differences. This can depend on the practical significance of the relevant part of the product, the extent to which it would be seen in use, or on other matters.”

At para [19] of his judgment in Marks and Spencer Plc v Aldi Stores Ltd, Judge Hacon explained:

"Points (5) and (6) were not intended to be sequential stages following (1) to (4) but further matters to be taken into account when conducting the comparison in stage (4). They may have been better labelled (4)(d) and (e)."

"Points (5) and (6) were not intended to be sequential stages following (1) to (4) but further matters to be taken into account when conducting the comparison in stage (4). They may have been better labelled (4)(d) and (e)."

"Decide the sector to which the products in which the designs are intended to be incorporated or to which they are intended to be applied belong"

M&S had proposed that the relevant sector was "Christmas liqueur in the UK". Aldi suggested "spirits and liqueurs in the UK." His Honour agreed that the decorations and snow indicated winter but did not see them as a constraint on the months in which sales could be made. Accordingly, he adopted Aldi's characterization.

"Identify the informed user and having done so decide (a) the degree of the informed user’s awareness of the prior art and (b) the level of attention paid by the informed user in the comparison, direct if possible, of the designs"

“[33] The designs are assessed from the perspective of the informed user. The identity and attributes of the informed user have been discussed by the Court of Justice of the European Union in PepsiCo Inc v Grupo Promer Mon-Graphic SA (C-281/10 P) [2012] FSR 5 at paragraphs 53 to 59 and also in Grupo Promer v OHIM (T-9/07) [2010] ECDR 7, (in the General Court from which PepsiCo was an appeal) and in Shenzhen Taiden v OHIM (T-153/08), EU: T:2010:248, judgment of 22 June 2010.

[34] Samsung submitted that the following summary characterises the informed user. I accept it and have added cross-references to the cases mentioned:

He (or she) is a user of the product in which the design is intended to be incorporated, not a designer, technical expert, manufacturer or seller (PepsiCo paragraph 54 referring to Grupo Promer paragraph 62; Shenzhen paragraph 46).

However, unlike the average consumer of trade mark law, he is particularly observant (PepsiCo paragraph 53);

He has knowledge of the design corpus and of the design features normally included in the designs existing in the sector concerned (PepsiCo paragraph 59 and also paragraph 54 referring to Grupo Promer paragraph 62);

He is interested in the products concerned and shows a relatively high degree of attention when he uses them (PepsiCo paragraph 59);

He conducts a direct comparison of the designs in issue unless there are specific circumstances or the devices have certain characteristics which make it impractical or uncommon to do so (PepsiCo paragraph 55).

[35] I would add that the informed user neither (a) merely perceives the designs as a whole and does not analyse details, nor (b) observes in detail minimal differences which may exist (PepsiCo paragraph 59).”

Applying that guidance His Honour decided that the informed user in this case would be a member of the UK public who purchases and consumes spirits and liqueurs. As the informed user is supposed to conduct a direct comparison of the designs, the learned judge opined that M&S’s bottle and Aldi’s would be used at home, as opposed to being used at two different points of purchase, so there would be an opportunity for direct comparison.

"Decide the designer’s degree of freedom in developing his design"

The judge referred to para [24] of Mr Justice Arnold's judgment in Whitby Specialist Vehicles Limited v Yorkshire Specialist Vehicles Limited [2014] EWHC 4242 (Pat), [2016] FSR 5:

“[24] … I considered the designer's degree of freedom in Dyson Ltd v Vax Ltd [2010] EWHC 1923 (Pat), [2010] FSR 39 at [32]-[37], where I concluded that design freedom may be constrained by (i) the technical function of the product or an element thereof, (ii) the need to incorporate features common to such products and/or (iii) economic considerations. I also concluded that both a departure from the existing design corpus and the production of a wide variety of subsequent designs were evidence of design freedom. Apart from emphasising that the degree of freedom to be considered was that of the designer of the registered design, the Court of Appeal appears to have agreed with this: [2011] EWCA Civ 1206, [2012] FSR 4 at [18]-[20].”

“[24] … I considered the designer's degree of freedom in Dyson Ltd v Vax Ltd [2010] EWHC 1923 (Pat), [2010] FSR 39 at [32]-[37], where I concluded that design freedom may be constrained by (i) the technical function of the product or an element thereof, (ii) the need to incorporate features common to such products and/or (iii) economic considerations. I also concluded that both a departure from the existing design corpus and the production of a wide variety of subsequent designs were evidence of design freedom. Apart from emphasising that the degree of freedom to be considered was that of the designer of the registered design, the Court of Appeal appears to have agreed with this: [2011] EWCA Civ 1206, [2012] FSR 4 at [18]-[20].”

After considering the evidence of M&S's lead designer, Judge Hacon concluded that the designer enjoyed a high degree of design freedom. The only constraint was that the neck of the bottle had to be wide enough to allow gold flakes to be inserted.

Judge Hacon quoted s.1C (1) of the Registered Designs Act 1949 (as amended):

“A right in a registered design shall not subsist in features of appearance of a product which are solely dictated by the product’s technical function.”

“A right in a registered design shall not subsist in features of appearance of a product which are solely dictated by the product’s technical function.”

He referred to paras [166] to[168]of his own judgment in Cantel in which he discussed art 8 (1) of the Community Design Regulation which is to similar effect:

“[166] It has been held by what was then the OHIM Board of Appeal that art.8 (1) of the Design Regulation deprives a feature of protection solely where the need to achieve the product’s technical function was the only relevant factor when the feature in question was selected to be part of the overall design. If aesthetic consideration played any part, art.8(1) does not bite. This is to be assessed objectively from the standpoint of a reasonable observer. See Lindner Recyclingtech GmbH v Franssons Verkstäder AB (R 690/2007-3) [2010] ECDR 1, at [28] to [36].

[167] Lindner was followed by Arnold J in Dyson Ltd v Vax Ltd [2010] EWHC 1923 (Pat); [2010] FSR 39, at [31] and apparently also approved by the Court of Appeal in Samsung Electronics (UK) Ltd v Apple Inc [2012] EWCA Civ 1339; [2013] FSR 9, at [31].

[168] Since art.8 (1), where it applies, deprives a feature of design protection, I think that such features are to be ignored in the assessment of overall impression under art.10 (1). This is to be contrasted with the approach to the related question of designer freedom under art.10 (2). As discussed below, assessment of the latter is not binary, but more flexible, with greater or lesser weight being attached to similarities or differences in appearance, as may be appropriate.”

“[166] It has been held by what was then the OHIM Board of Appeal that art.8 (1) of the Design Regulation deprives a feature of protection solely where the need to achieve the product’s technical function was the only relevant factor when the feature in question was selected to be part of the overall design. If aesthetic consideration played any part, art.8(1) does not bite. This is to be assessed objectively from the standpoint of a reasonable observer. See Lindner Recyclingtech GmbH v Franssons Verkstäder AB (R 690/2007-3) [2010] ECDR 1, at [28] to [36].

[167] Lindner was followed by Arnold J in Dyson Ltd v Vax Ltd [2010] EWHC 1923 (Pat); [2010] FSR 39, at [31] and apparently also approved by the Court of Appeal in Samsung Electronics (UK) Ltd v Apple Inc [2012] EWCA Civ 1339; [2013] FSR 9, at [31].

[168] Since art.8 (1), where it applies, deprives a feature of design protection, I think that such features are to be ignored in the assessment of overall impression under art.10 (1). This is to be contrasted with the approach to the related question of designer freedom under art.10 (2). As discussed below, assessment of the latter is not binary, but more flexible, with greater or lesser weight being attached to similarities or differences in appearance, as may be appropriate.”

Aldi had argued that (1) the distribution of gold flakes, (2) the use of gold flakes; (3) leaving the upper, curved portion of the bottle clear of markings and (4) putting the integrated light source in the punt (the dimple) at the base of the bottle were dictated solely by function. His Honour disagreed. In his view, all four features were aspects or consequences of aesthetic choices made by the designer. He acknowledged that the use of gold flakes was necessary once the designers had decided to simulate snow but that did not give the gold flakes a technical function.

Labelling

[16] Actually what the judge said about the trade mark being on the front of the Samsung tablets was said in the context that Apple was contending that a feature of the registered design was ‘A flat transparent surface without any ornamentation covering the front face of the device up to the rim.’ He said:

‘[113] All three tablets are the same as far as feature (ii) is concerned. The front of each Samsung tablet has a tiny speaker grille and a tiny camera hole near the top edge and the name Samsung along the bottom edge.

[114] The very low degree of ornamentation is notable. However a difference is the clearly visible camera hole, speaker grille and the name Samsung on the front face. Apple submitted that the presence of branding was irrelevant …. However in the case before me, the unornamented nature of the front face is a significant aspect of the Apple design. The Samsung design is not unornamented. It is like the LG Flatron. I find that the presence of writing on the front of the tablet is a feature which the informed user will notice (as well as the grille and camera hole). The fact that the writing happens to be a trade mark is irrelevant. It is ornamentation of some sort. The extent to which the writing gives the tablet an orientation is addressed below.

[115] The Samsung tablets look very close to the Apple design as far as this feature is concerned but they are not absolutely identical as a result of a small degree of ornamentation.’

[17] So what the judge was considering was the fact that unlike the design, the front face had some sort of ornamentation which happened to be a trade mark (plus speaker grill and camera hole). Little turned on it in his view, he called it ‘a small degree of ornamentation.’ But it was a difference.

[18] I think the judge was correct here. If an important feature of a design is no ornamentation, as Apple contended and was undisputed, the judge was right to say that a departure from no ornamentation would be taken into account by the informed user. Where you put a trade mark can influence the aesthetics of a design, particularly one whose virtue in part rests on simplicity and lack of ornamentation. The judge was right to say that an informed user would give it appropriate weight - which in the overall assessment was slight. If the only difference between the registered design and the Samsung products was the presence of the trade mark, then things would have been different.

[19] Much the same goes for the Samsung trade mark on the back of the products. Apple had contended that a key feature was ‘a design of extreme simplicity without features which specify orientation.’ Given that contention the judge can hardly have held that an informed user would completely disregard the trade marks both front and back which reduce simplicity a bit and do indicate orientation.”

While it was no part of M&S’s case that its designs lacked ornamentation, the judge held that the word “Infusionist" was clear enough to make an impression. It was a presence and a difference from the registered designs. However, he found the words “The” and “Small Batch” to be less conspicuous and so played no significant additional part in the overall impression of the designs.

Date of Comparison

Relying on s.14 (2) of the Act as amended, the judge held that the date for making the comparison between a registered design and an allegedly infringing article was the priority date or as the case may be the date of registration.

Making the Comparison

Judge Hacon relied on para [35] of Lord Justice Jacob's judgment in Procter & Gamble Co v Reckitt Benckiser (UK) Ltd. and para [172] of his own judgment in Cantel for guidance in assessing infringement. Lord Justice Jacob had said:

“i) For the reasons I have given above, the test is ‘different’ not ‘clearly different.’

ii) The notional informed user is ‘fairly familiar’ with design issues, as discussed above.

iii) Next is not a proposition of law but a statement about the way people (and thus the notional informed user) perceive things. It is simply that if a new design is markedly different from anything that has gone before, it is likely to have a greater overall visual impact than if it is ‘surrounded by kindred prior art.’ (Judge Fysh's pithy phrase in Woodhouse UK plc v Architectural Lighting Systems [2006] RPC 1, para 58). It follows that the ‘overall impression’ created by such a design will be more significant and the room for differences which do not create a substantially different overall impression is greater. So protection for a striking novel product will be correspondingly greater than for a product which is incrementally different from the prior art, though different enough to have its own individual character and thus be validly registered.

iv) On the other hand it does not follow, in a case of markedly new design (or indeed any design) that it is sufficient to ask ‘is the alleged infringement closer to the registered design or to the prior art’, if the former infringement, if the latter not. The tests remains ‘is the overall impression different?’

v) It is legitimate to compare the registered design and the alleged infringement with a reasonable degree of care. The court must ‘don the spectacles of the informed user’ to adapt the hackneyed but convenient metaphor of patent law. The possibility of imperfect recollection has a limited part to play in this exercise.

vi) The court must identify the ‘overall impression’ of the registered design with care. True it is that it is difficult to put into language, and it is helpful to use pictures as part of the identification, but the exercise must be done.

vii) In this exercise the level of generality to which the court must descend is important. Here, for instance, it would be too general to say that the overall impression of the registered design is ‘a canister fitted with a trigger spray device on the top.’ The appropriate level of generality is that which would be taken by the notional informed user.

viii) The court should then do the same exercise for the alleged infringement.

ix) Finally the court should ask whether the overall impression of each is different. This is almost the equivalent to asking whether they are the same - the difference is nuanced, probably, involving a question of onus and no more.”

“i) For the reasons I have given above, the test is ‘different’ not ‘clearly different.’

ii) The notional informed user is ‘fairly familiar’ with design issues, as discussed above.

iii) Next is not a proposition of law but a statement about the way people (and thus the notional informed user) perceive things. It is simply that if a new design is markedly different from anything that has gone before, it is likely to have a greater overall visual impact than if it is ‘surrounded by kindred prior art.’ (Judge Fysh's pithy phrase in Woodhouse UK plc v Architectural Lighting Systems [2006] RPC 1, para 58). It follows that the ‘overall impression’ created by such a design will be more significant and the room for differences which do not create a substantially different overall impression is greater. So protection for a striking novel product will be correspondingly greater than for a product which is incrementally different from the prior art, though different enough to have its own individual character and thus be validly registered.

iv) On the other hand it does not follow, in a case of markedly new design (or indeed any design) that it is sufficient to ask ‘is the alleged infringement closer to the registered design or to the prior art’, if the former infringement, if the latter not. The tests remains ‘is the overall impression different?’

v) It is legitimate to compare the registered design and the alleged infringement with a reasonable degree of care. The court must ‘don the spectacles of the informed user’ to adapt the hackneyed but convenient metaphor of patent law. The possibility of imperfect recollection has a limited part to play in this exercise.

vi) The court must identify the ‘overall impression’ of the registered design with care. True it is that it is difficult to put into language, and it is helpful to use pictures as part of the identification, but the exercise must be done.

vii) In this exercise the level of generality to which the court must descend is important. Here, for instance, it would be too general to say that the overall impression of the registered design is ‘a canister fitted with a trigger spray device on the top.’ The appropriate level of generality is that which would be taken by the notional informed user.

viii) The court should then do the same exercise for the alleged infringement.

ix) Finally the court should ask whether the overall impression of each is different. This is almost the equivalent to asking whether they are the same - the difference is nuanced, probably, involving a question of onus and no more.”

As point (iii) of Lord Justice Jacob's analysis introduced consideration of the design corpus into the assessment of infringement, Judge Hacon said:

“[170] Designs which are strikingly new in every way will be unusual. More often some features will be commonly found in the design corpus, others not. In such a case the correct approach is to give little or no weight to common features. In Grupo Promer Mon Graphic SA v OHIM (Case T-9/07) EU: T:2010:96; [2010] ECDR 7, the General Court said at [72]:

‘… in so far as similarities between the designs at issue relate to common features…, those similarities will have only minor importance in the overall impression produced by those designs on the informed user.’”

“[170] Designs which are strikingly new in every way will be unusual. More often some features will be commonly found in the design corpus, others not. In such a case the correct approach is to give little or no weight to common features. In Grupo Promer Mon Graphic SA v OHIM (Case T-9/07) EU: T:2010:96; [2010] ECDR 7, the General Court said at [72]:

‘… in so far as similarities between the designs at issue relate to common features…, those similarities will have only minor importance in the overall impression produced by those designs on the informed user.’”

The Design Corpus

The judge noted that the above bottles represented only a small proportion of the totality within the design corpus in October 2020. He summarized the design corpus as follows:

"[78] Excluding M&S’s products, four bottles with an integrated light were marketed before December 2020 but none with a shape like that of the RDs in suit. Five members of the corpus had a snow effect of some sort, none with a bottle shape similar to that of the RDs in suit. Two among the foregoing had both a snow effect and an integrated light.

[79] Aldi drew attention to the Crosby and Thatcher gin bottles shown in paragraph 71 above (the latter is in the lower row, second from the right). Within the large corpus, five further examples were found having a shape very similar to these two (Glen Wyvis, Perth, Koppaberg, Morrisons and Todley’s). All have relatively high shoulders and are visibly different from the 'botanics' shape of the RDs in suit. None has either a snow effect or an integrated light.

[75] Saverglass, the manufacturer of the bottles supplied to M&S, has a UK registered design for its botanics shape, registered as of 18 November 2015. It forms part of the corpus:

[76] Of the totality of the design corpus and excluding M&S designs made available in the grace period, only the M&S 2019 Snow Globe has the botanics shape and a snow effect (no integrated light)."

Conclusion

At para [80] the learned judge listed the features that Aldi's bottles had in common with M&S's registered designs:

"(1) The identical shapes of the two bottles. The informed user would pay little attention to the fact that both have in part straight sides. That is true of the vast majority of the spirit bottles shown in the evidence. The informed user would take into account that for economic reasons the range of bottle shapes for spirits and liqueurs does not extend to every functional and aesthetic possibility. However, this would not detract from the apparent identicality in shape when measured against the design corpus as a whole

(2) What appear to be the identical shapes of the two stoppers.

(3) A winter scene over the entirety of the straight portion of the side, consisting in one case entirely, and in the other case mostly, of tree silhouettes.

(4) In the case of UK 80 and 84, a snow effect.

(5) In the case of UK 82 and 84, an integrated light."

"(1) The identical shapes of the two bottles. The informed user would pay little attention to the fact that both have in part straight sides. That is true of the vast majority of the spirit bottles shown in the evidence. The informed user would take into account that for economic reasons the range of bottle shapes for spirits and liqueurs does not extend to every functional and aesthetic possibility. However, this would not detract from the apparent identicality in shape when measured against the design corpus as a whole

(2) What appear to be the identical shapes of the two stoppers.

(3) A winter scene over the entirety of the straight portion of the side, consisting in one case entirely, and in the other case mostly, of tree silhouettes.

(4) In the case of UK 80 and 84, a snow effect.

(5) In the case of UK 82 and 84, an integrated light."

In His Honour's judgment and with the design corpus in mind, each of those similarities would appear significant to the informed user and cumulatively they would be striking. He acknowledged the following differences:

"(1) The winter scene of the RDs in suit is in white only and features a stag and a doe. On the Aldi bottles the scene is in white and a colour with trees only.

(2) The Aldi bottle has the “Infusionist” branding. The RDs in suit have none.

(3) The foregoing two features of the Aldi bottle give it a front. There is no front to the RDs in suit.

(4) The Aldi winter scene is brighter and busier than that on the RDs in suit.

(5) The Aldi stoppers have a watch strap label with the Aldi logo on the top, the RDs in suit do not.

(6) The Aldi stoppers are darker in shade than those of the RDs in suit."

He reminded himself that the statutory test was whether the registered designs and Aldi bottles produced a different overall impression and in his judgment they did not, The differences were there but they were differences of relatively minor detail which did not affect the lack of difference in the overall impressions produced by the Aldi bottles on the one hand and each of the registered designs in suit on the other.

Further Information

Anyone wishing to discuss this case may call me on 020 7404 5252 during normal office hours or send me a message through my contact form in the meantime.

Comments