Jane Lambert

Patents Court (Michael Tappin KC) Merck Serono SA v Comptroller-General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks [2023] EWHC 3240 (Ch) (19 Dec 2023)

This was an appeal by Merck Serono SA ("Merck") against Mary Taylor's refusal to grant a supplementary protection certificate ("SPC") in respect of cladribine (see Merck Serono S.A. v Comptroller 26 May 2023 BL O/0484/23)). The appeal came on before Mr Michael Tappin KC sitting as a deputy judge of the High Court on 12 Dec 2023. By his judgment in Merck Serono SA v Comptroller-General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks [2023] EWHC 3240 (Ch) (19 Dec 2023, the learned deputy judge dismissed Merck's appeal.

Supplementary Protection Certificates

In Supplementary Protection Certificates I wrote:

"A supplementary protection certificate ..... is an intellectual property right ("IPR") that protects the active ingredients in pharmaceutical or plant protection products. The right comes into force upon the expiry of a patent for such a product. The rationale for SPCs is that new pharmaceutical and plant protection products cannot be marketed unless and until they are found to be safe by the relevant national or European authorities. Evaluating the safety of a new drug or plant protection product can take time. As the maximum term of a patent is 20 years the time waiting for such evaluation reduces the effective term of the monopoly. The purpose of an SPC, as Lord Justice Floyd explained in Teva UK Ltd and others v Gilead Sciences, Inc [2019] EWCA Civ 2272 (19 Dec 2019), is, therefore, to compensate the patentee for such lost time by protecting the active ingredient of the pharmaceutical or plant protection patent for up to 5 years (or in the case of a product used for treating children a further 6 months) after the expiry of the patent."

The Facts

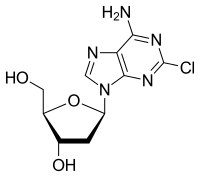

Merck applied to the European Patent Office for a European patent for a Cladribine regimen for treating multiple sclerosis on 20 Dec 2005. Its application was successful.

EP 1827461 B1 was granted for the invention on 29 Feb 2012. The patent will expire on 19 Dec 2025.

On 12 Feb 2018, Merck applied to the UK Intellectual Property Office for an SPC for

cladribine under

Regulation (EC) No 469/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 May 2009 concerning the supplementary protection certificate for medicinal products. It filed the patent and marketing authorization EU/1/17/1212 for a product called MAVENCLAD (the active ingredient of which is cladribine) under SPC number

SPC/GB18/007. The examiner objected to the application under

art 3 (d) of the Regulation on the ground that there had been two previous marketing authorizations for medicinal products containing cladribine as an active ingredient. Those were PL 00242/0232 issued on 3 Feb 1995 for "LEUSTAT" and EU/1/04/275 issued on 14 April 2004 for "LITAK". They were for medicinal products indicated for the treatment of hairy cell leukaemia. Merck was unable to persuade the examiner in correspondence and appealed to the Comptroller.

Proceedings before the Comptroller

The appeal came on before Mary Taylor on behalf of the Comptroller on 8 March 2023. She considered the Regulation and the judgments of the Court of Justice of the European Union ("CJEU") on its interpretation. Merck had referred her to

Case C-130/11 Neurim Pharmaceuticals (1991) Ltd v Comptroller-General of Patents [2013] RPC 23, [2012] EUECJ C-130/1 in which the Court of Appeal had asked the following question:

"In interpreting Article 3 of [the SPC Regulation], when [an MA] (A) has been granted for a medicinal product comprising an active ingredient, is Article 3 (d) to be construed as precluding the grant of an SPC based on a later [MA] (B) which is for a different medicinal product comprising the same active ingredient where the limits of the protection conferred by the basic patent do not extend to placing the product the subject of the earlier MA on the market within the meaning of Article 4?"

The Court replied:

"Articles 3 and 4 of Regulation (EC) No 469/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 May 2009 concerning the supplementary protection certificate for medicinal products must be interpreted as meaning that, in a case such as that in the main proceedings, the mere existence of an earlier marketing authorisation obtained for a veterinary medicinal product does not preclude the grant of a supplementary protection certificate for a different application of the same product for which a marketing authorisation has been granted, provided that the application is within the limits of the protection conferred by the basic patent relied upon for the purposes of the application for the supplementary protection certificate."

The CJEU retreated from

Neurim in Case C‑673/18

Santen SAS v Directeur Général de l’Institut National de la Propriété Industriel[e ECLI:EU: C:2020:531, EU: C:2020:531, [2020] EUECJ C-673/18. Merck accepted that if

Santen was to be followed then its application for an SPC would have to be refused. However, Merck contended that

Neurim was good law when it filed its application and that

Santen should not be applied because it undertook the development of its product with the reasonable expectation that it would be entitled to an SPC in accordance with

Neurim.

The hearing officer rejected Merck's contention. She said at para [50]:

"Santen clearly provides that a marketing authorisation cannot be considered the first marketing authorisation where it covers a new therapeutic application of the product. As I have noted above, there are two earlier marketing authorisations for cladribine and therefore, I conclude that the marketing authorisation for MAVENCLAD, on which the application relies, is not the first authorisation to place the product, cladribine, on the market as a medicinal product. Thus, the application does not satisfy the requirements of Article 3 (d)."

She dismissed Merck's SPC application.

The Appeal

Merck appealed to the Patents Court on the following grounds:

Ground 1: Santen should be understood as having ex nunc rather than ex tunc effect. Alternatively, it should be treated as such because of the expectations of those in the industry as to the continued application of the law as stated in Neurim. Further, Merck's own circumstances gave rise to an individual expectation that it would be granted an SPC in accordance with the law as stated in Neurim and that the UKIPO and Patents Court should give effect to that expectation.

Ground 2: The facts of this application could be distinguished from Santen and so Santen should not apply on the present facts.

Ground 3 Santen had been wrongly decided.

Geound 1 Whether Santen applies ex tunc or ex nunc

Merck argued that it had invested in the development of MAVENCLAD with the reasonable expectation that it would be granted an SPC for its active ingredient It said that it would not have made such an investment had it known that the law would change. The hearing officer had doubted that Merck's work in bringing MAVENCLAD to the market had been undertaken solely to obtain an SPC. Mr Tappin, however, was willing to proceed on the basis that the expectation of an SPC would have played a part a part in Merck's decision-making.

Before considering Merck's first ground of appeal, the learned deputy judge sought to satisfy himself that the CJEU could depart from its previous decisions and whether its decisions could take effect ex nunc rather than ex nunc. If it is not obvious from the context "ex tunc" means literally "right now": that is to say, a change in the law applies with immediate effect even if the change had not been anticipated. "Ex nunc" means "from now on" and applies to situations that may arise after such change.

As to whether the CJEU could reverse its previous decisions, Mr Tappin was referred to the Advocate-General's opinion in Case C-10/89 Hag II at [67], He concluded that it might be rare for the CJEU not to follow its previous decisions but Santen was not without precedent. The court's power to do so had been established many years ago.

Similarly, he found that although it was rare for the court to order its decisions to take effect ex nunc it was entitled to do so. He considered whether Santen took effect ex tunc and not ex nunc. There was no express indication that it was to apply ex nunc. Nor was there anything in the judgment to raise an inference to that effect. He therefore agreed with the hearing officer that Santen applied ex tunc.

Merck had contended that the expectations of the industry as to the continuation of the law should be taken into account and that the courts of this jurisdiction were entitled to decide that a temporal restriction on the application of the

Santen judgment should be imposed. Merck cited the judgment of the Swiss Supreme Court of 11 June 2018 in case 4A_576/2017 which held that a change in the law should not be applied retrospectively to prevent the grant of an SPC. Mr Tappin rejected that contention. The Swiss courts may not have been obliged to follow decisions of the CJEU before 31 Dec 2020 but the English courts were. It was clear from Case 61/79

Amministrazione delle finanze dello Stato v Denkavit italiana Srl. ECLI:EU: C:1980:100 that only the CJEU had power to impose a temporal limitation on the effects of its own judgments. It had not done so in

Santen and it was not open to Mr Tappin to decide to impose one.

Merck also referred to a statement of the Enlarged Board of Appeal in G9/93 that "on purely procedural issues there may be reasons of equity for not applying to pending cases the law as thus interpreted. In cases currently pending before the EPO and relying on decision G1/84, which has now been followed for many years." The deputy judge's view was that this was at most "a further example of the highest tribunal in a system recognising that it may be appropriate for its decisions to apply ex nunc and deciding to impose a temporal restriction in a particular case." Also, it was clear that it applied only to procedural matters.

Mr Tappin invited the parties to explore the practice in England when the Supreme Court reverses its own case law. He noted that although the

Practice Statement (Judicial Precedent) [1966] 1 WLR 1234. requires the Court to "bear in mind the danger of disturbing retrospectively the basis on which contracts, settlement of property, and fiscal arrangements have been entered into" it did "not mean that if the Supreme Court decides, having considered such matters, to depart from a previous decision, those who are adversely affected are entitled to ask the courts to treat them as if the change had not been made, on the basis of an expectation that the law would remain unchanged." He added at para [70]:

"Ir is striking that no authority has been identified by Merck to support the proposition that a party can avoid the effects of a change in the interpretation of substantive law which is not expressed to be ex nunc by showing that it acted on the basis of the previous interpretation of the law."

Finally, Merck's contention was tested by considering whether it would apply to a revocation application by a third party who was relying on Santen. Mr Tappin observed in para [77]:

"The question of validity of an SPC granted on Merck's application will, apparently, not turn on the provisions of the Regulation as interpreted by the courts, but on a battle of legitimate expectations between Merck and whoever the challenger turns out to be. That cannot be right."

He concluded that Merck's expectation that it would be granted an SPC based on

Neurim, and its reliance on that when deciding to revive its development program, could not give rise to a right to an SPC. The CJEU's judgment in

Santen operated

ex tunc.

Ground 2 - Whether Santen could be distinguished

Mr Tappin held at para [38] that it could not. Santen was a ruling on the interpretation of art 3 (d) of the Regulation. It could have been decided on its own facts but the Advocate-General made clear that Neurim should not be followed and the CJEU made clear that it would follow his advice.

Ground 3 - Whether Santen was wrongly decided

Comments